Győr is an industrial city: the factories operating here have defined both its society and its economy for centuries. The Győr Distillery can be considered the oldest one, since it started operating in 1884, and is the only one among the many factories that have been operating in the same place since its foundation. There are families that have been working there for generations — a fact that makes the Győr Distillery an important part not only of the city’s history and industrial heritage, but also of the people’s work culture, way of living and value system.

Győr is the seat of one of Hungary’s 19 counties, Győr-Moson-Sopron. The town is located in the north-western part of Hungary, at the same distance from Vienna, Bratislava, and Budapest, approximately an hour and a half by car. Győr is situated in a flat area, but smaller hills border it to the south. The downtown view is defined by three rivers (one of the Danube’s tributaries, Rába, and Rábca) and their meeting within the city along with the low-altitude Káptalandomb in the downtown.

Győr is one of the industrial centres of Hungary. Since its foundation, the history, economy, and society of the city have been determined by trade and then industry. However, nowadays, few of the long-established factories remain, and the Győr Distillery and Refinery Co -in which we focus- is the only one that operates on the site of its founding (1884).

The first factories in Győr appeared before the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, but they ceased to exist after a few years of operation. By the 1860s, the city had become one of the most important transhipment and forwarding centres of the Hungarian grain trade to the west. After constructing the railway network, this role was taken over by the country’s capital (Budapest). The people of Győr found a new way to prosper in industrialisation and the establishment of factories. The forward-thinking leaders of the city have done everything they could to create the infrastructural conditions necessary for economic restructuring. Agriculture was the most crucial sector of historical Hungary. It is understandable, therefore, that the factories established in Győr in the second half of the 19th century adapted to the country’s conditions and processed agricultural raw products (mills, vinegar factories, vegetable oil factories) and served the everyday needs of the rural population (agricultural machinery factories, matchmakers, stoves).

The emblematic enterprises of the one and a half-century long history of the city’s manufacturing industry primarily came from the territory of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, typically from Bohemia, Moravia, and Austria. However, the distillery in Győr was exceptionally founded by local crop traders. The construction of one of the most modern distilleries in the Monarchy -due to a faulty business policy perception- consumed the entire share capital, so the company drifted to the brink of bankruptcy in a short time. From this situation, in 1895, the Lederer brothers saved the factory. The Lederer family, which dominated the Central European spirits industry from the end of the 19th century until World War I, formed a huge conglomerate by acquiring several distilleries, liqueur, and yeast factories in Hungary, Lower Austria, Upper Hungary, and Galicia. One of its subsidiary companies was the Győr Distillery and Refinery Co., under the leadership of August Lederer, who bought the factory from the fabulous dowry of his wife, Serena Pulitzer, and directed the distillery until his death in 1936. Furthermore, he started several other companies in Győr, including the Hungarian Wagon and Machine Factory, which decisively determined the city’s economic life in the 20th century.

In 1938, the Hungarian state monopolised the production of spirits and, in addition to compensating owners, expropriated the largest distilleries in the country, including the factory in Győr. At the end of World War II, a series of bomb attacks on the city destroyed about 90% of the distillery’s buildings and equipment. It also became questionable whether it was at all worth rebuilding the company in its original location for a while.

Besides alcohol refining, one of the factory’s side activities was the production of feed yeast. The so-called torula factory was noisy and smelly, disturbing nearby residents. An even bigger problem was that the remaining large mass of molasses was discharged into the Danube without treatment, thus making the Győr Distillery the second-largest living water pollutant in the city to the city sewer network. (This problem has, of course, disappeared since then.) The question of the factory’s relocation to the city’s outskirts was first raised after it was almost completely destroyed during World War II. This idea re-emerged in the 1990s, but it was eventually removed from the agenda due to high costs.

After the political and economic changes of the 1990s, most of the long-established factories in Győr closed down. On the site of the former textile factories in Győr -except the glove factory- stores of large commercial networks were built, and most of the buildings disappeared. The oil plant was demolished, its chimneys were blown up, and residential houses were erected in its place. From the once famous biscuit factory, only the warehouse building survived. However, the distillery remained in its original location and continues to operate for nearly a century and a half.

After the collapse of socialism in 1989-90, the city gave home to Central Europe’s first industrial park in 1992. One of Audi’s largest plants, employing nearly 12,000 people, has been operating here since 1994, but other multinational companies (such as Philips) also have factories in the city. In addition to international companies, the presence of Hungarian ones is also significant. The majority of employees in Győr work for industrial enterprises or in the supplier sector serving the industry.

The transformation of Győr to a prosperous industrial centre meant not only changes in the architecture and urban planning of the city, but also the making of new social classes and communities. To this end, a more substantial change was that, during this period, the demand for labor force for the manufacturing industry increased significantly. This demand could be covered by the settlement of workers, which resulted in the increase of the population of the city at a fast and intense pace.

The socio-economic structure of Győr is founded on its 150-year-long industrial history and heritage. During this time, a certain work culture and way of life have been created in the city. In the period of socialism, industry and its forced development were of symbolic significance: it was one of the primary means of forming and developing the socialist ideal and the socialist image of man: the worker. In this era, politics also saw art as a means of strengthening the political system. Social realism was born in this socio-political space and, in many cases, was able to showcase real artistic value. The defining theme of social realism was industry, the factory and the worker. Despite the fact that, in Győr, only a few social realist works of art were born, they can still be detected mainly in the field of architecture (e.g. train station building) and public space sculptures.

The work culture and the shaping of the worker are a valuable intangible heritage feature of the city, as UNESCO defines it — that is “the practices, representations, expressions, and skills transmitted from generation to generation, which provide people with a sense of identity and continuity.” For the case of Gyor, the knowledge, practices, and skills relevant to the understanding of industrial processes, and the material legacies of industrial production are of fundamental importance. This industrial heritage is an interconnected part of the city, belonging to the urban environment’s past, present and future, but more importantly to people, as it is directly associated with memories, ways of living, traditions and labour movements. Intangible heritage values have always been tied to collective identities; from neighbourhoods to cities and sometimes regions, they have affected how physical, visual and perceived boundaries are formulated. Considering intangible cultural heritage in the context of industrial heritage is important, because it generates a richness of everyday rituals and ways of life, and structures identities.

Lederer and Schiele

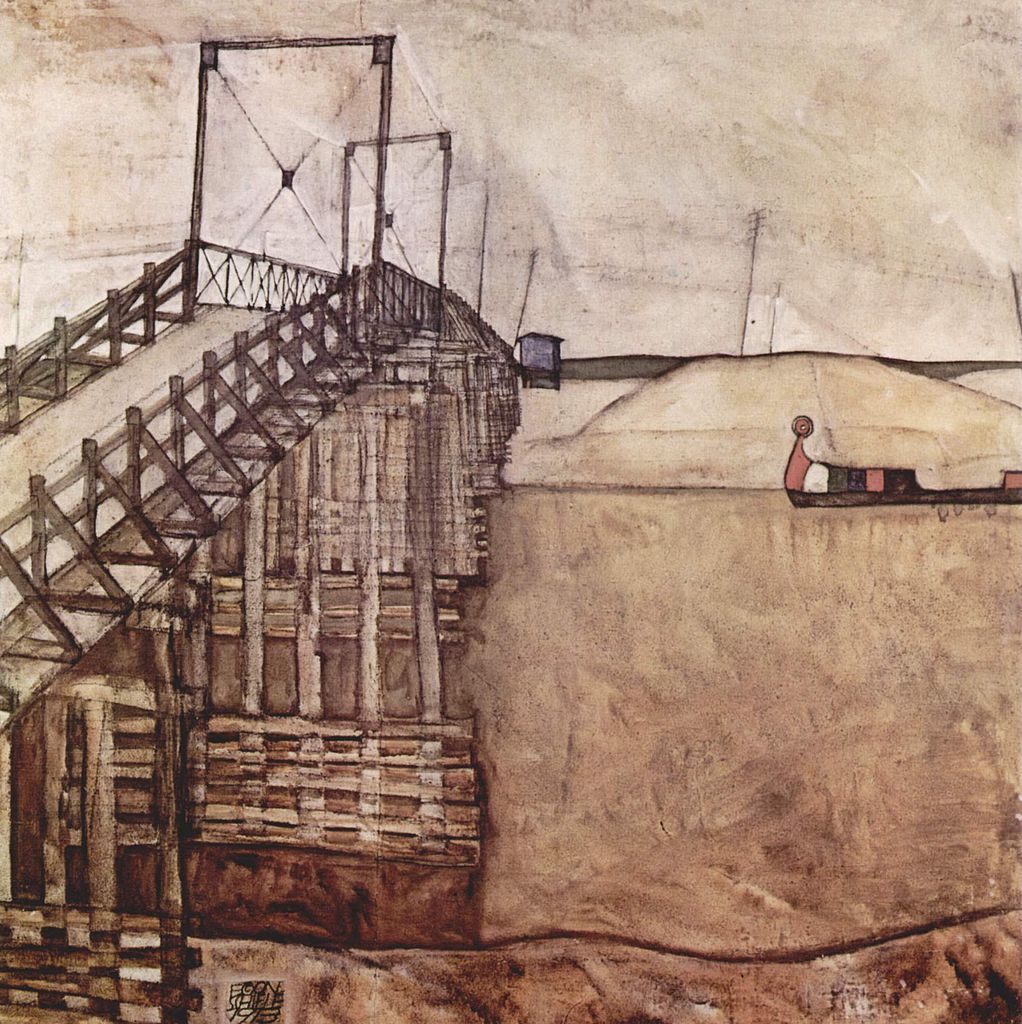

The former owner of the Győr distillery, August Lederer (1857-1936), and his wife, Serena Lederer (1867-1943), were important art collectors and patrons of their time. They had a wide network, and were one of Gustav Klimt‘s primary customers. The famous painter drew their attention to Egon Schiele, the then young, emerging artist, whom the Lederer family had invited to Győr, and provided with a residence and a studio in the distillery. During that period, Schiele created his painting which is related to Győr, The Bridge.

Győr Artists’ Colony

The Győr Artists’ Colony was established in 1969 to increase the number of contemporary art events in the city and strengthen the local population’s patriotism. From 1975 onwards, well-established artists also took part in the artists’ colony. In 1976, the idea arose that the city’s industrial potential should be exploited in this area as well. In 1976, the artists’ colony in Győr was transformed into a sculpture colony called RÁBA Symposium, which started operating at the premises and Rába Wagon and Machine Factory sites. The change of concept and professional artists’ invitation resulted in a significant difference in quality. New, primarily large-scale geometric metal sculptures with unusual shapes have been created, but the purely sculptural era of the artists’ colony ended in 1978. During these three years, it became clear that it was difficult for the factory to meet the creators’ material, technological and professional needs. Besides, primarily geometric abstract works with industrial technology (kinetic sculptures, mobiles, large-scale chrome-steel reliefs, and stainless-steel space sculptures, and statuettes) did not fit into the cultural ideology of socialism. (The sculptures were exhibited in public for some time after the change of Hungary’s political system in the 1990s.) After many transformations, the operation of the artists’ colony has been the responsibility of the city museum since 1996.

Besides its industrial character, Győr is also rich in cultural inspiration. Such as the world-famous Ballet Company of Győr, the EFFE Award-winning Five Churches Festival, the ecclesiastical-sacral center in the downtown, the Vaskakas Puppet Theater, which is one of the highest listed professional puppet theatres in Hungary, the Rómer Flóris Museum, with the most extensive collection on the countryside, the civic initiatives-based Design Week and the newly launched Design Campus, or form-breaking cultural venues such as the “Beton” in a former military shelter or the Torula Art Space, and many other cultural groups, projects and communities. The meeting of the three rivers in the downtown gives a unique and inspiring atmosphere such as the contradiction between the baroque downtown and the suburbs full of panel houses.

Géczy, N., Komlósi, L. (2016). “Challenges of Urban Design Driven by Dynamics of Socio-Cultural and Urban-Space Needs: A Case Study of the City of Győr, Hungary. Matiu, O. (ed.). Cities: The Fabric of Cultural Memories. Confrontation or Dialog?, Proceedings of the Tenth Interdisciplinary Conference of the University Network of the European Capitals of Culture. Wroclaw, Poland: Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu Press (published online).

Investment Bank, E., Gerőházi, É., Tosics, I. (2019). Győr: How to compete with capital cities. Publications Office of the EU (published online).

Miller, T. (2019). “Art in Hungary, 1956-1980: Doublespeak and Beyond (Book Review)”. ARTMargins (published online).

Oevermann, H., Mieg, H. (2015). Industrial Heritage Sites in Transformation. Clash of Discourses. New York: Taylor and Francis Group (WorldCat).

Sasvári, E., Hornyik, S., Turai, H. et al. (eds., 2018). Art in Hungary, 1956–1980: Doublespeak and Beyond, London: Thames & Hudson (WorldCat).

TICCIH: The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (July 2003). The Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage (published online).

Research on local history, cultural heritage and traditions: Gergő Paukovics

Research on open access repositories: Gergő Paukovics, Revekka Kefalea

Review and semantic enrichment: Mina Karatza, Nikos Pasamitros, Revekka Kefalea

Last update: 27 June 2021.

During the Győr Art Residency (July 2021), the artists-in-residence worked and currently (15-31 October 2021) exhibit their artworks at the Torula Art Place, which is Győr’s new cultural and community space, operating since 2017. It is located in one of the halls of the Győr Distillery, which is not used for industrial production anymore. It took its name from one of the by-products of alcohol production, the so-called torula yeast, which was produced here. On the one hand, Torula’s aim is to support young artists at the beginning of their careers, and thus promote the creation of fine and performing arts productions, and, on the other, to promote the accessibility and reception of works of art.

Torula’s mission is to stimulate participation in cultural life, to arouse interest, and involve a broad audience on current contemporary art issues. This can serve as a breeding ground for dialogues and debates between community and professionals. Torula’s long-term goal is to create a community space for young people, artists, and those interested in contemporary art. Gather not only to spend time and meet, but also to think and be inspired both by space and people. Consequently, to become an open and accessible space that accepts, brings together, presents, opens up individuals and communities, artists and artistic trends, cities and worlds, minds and hearts. In Torula – in addition to temporary exhibitions, creative camps, workshops, conferences, and events of creative communities that value uniqueness – there are also artist studios to be found. Meetings and community events with artists working in these studios will be an integral part of ECHO II’s art residency program.